Le Corbusier versus Hilbersheimer on Modern town planning: an inquiry into theory for the city of tomorrow. With reference to their proposals and design for Paris and Berlin.

Humans have always taken great pride in the future, from merely thinking about it, to the contribution they have made to it. Artists endeavour to create a new artistic movement which will change how we think, engineers endeavour to design a new structural joint which will revolutionise how we build, so perhaps with this knowledge it comes with little surprise then, that architects have always been fixated with designing the future of not only the built environment, but of human behaviour. The 20th century serves as an interesting time for architects, therefore: a technological revolution, never seen before transportation methods becoming everyday occurrences, and of course two world wars which not only changed the world’s social and political dynamics but changed how every person lived and worked; gone were the days of rich and poor, urban or country. These were the days of equality; these were the days of utopia. Both Le Corbusier and Ludwig Hilberseimer proposed their vison of the utopian city. Both were then applied to European capitals, both were never built, yet Le Corbusier’s design was designed for a near future, whereas Hilberseimer was focused on designing a completed city which would last forever, perhaps a future which would never come.

Le Corbusier almost needs no introduction. This Swiss-born architect started out his working life by engraving watches in his small home town, and learned the history of art and the skill of hand- drawing from Charles L’Eplatternier whom Le Corbusier would go on to call his only teacher, and was the person who suggested that Le Corbusier should go on to study architecture due to his natural talent. During this time, Le Corbusier travelled extensively in the Mediterranean and in Central Europe, which gave him a strong insight into the use of light in architectural spaces as well as geometry, learned from such greats as Andrea Paddadio. Le Corbusier is the father of modern architecture, designing pieces of furniture to houses and the United Nation’s headquarters: is it even a surprise that Le Corbusier always had his eyes on the designing of cities, and the dictation of the city-dweller’s lifestyle?

In contrast, Ludwig Hilberseimer was a German urban planner who set up the city planning department at the Bauhaus in Dessau and later moved to the United States to flee persecution from the Nazi party, who had a strong hatred for modernism, let alone futurism. Upon his arrival in the United States, Hilberseimer started working for Mies van der Rohe, and was made the director of Chicago’s city planning department and the head of the department of urban planning at IIT College of Architecture. Hilberseimer was a logical thinker. “Within the history of architecture there is no more drastic representation of the generic ethos of capitalistic production and the urban consequences of economic reasoning than the work of Ludwig Hilberseimer” [1]. Hilberseimer was interested in a rational city plan, derived from capitalist production and put art, culture and greenspace on the back-burner.

Growing up in a town which relied on artistic and craftsman-like skill, the rise of machines and automation would cause anyone great concern. “For Le Corbusier, the industrial revolution was a personal experience.” [2] Le Corbusier wanted to find a city in which the workers of industry were as harmonious as people from the arts. His approach was scientific, not to factor in terrain, to go against every other city whose design has been made up of many decisions of many people over many years, and to have his ideal city designed by one individual. He came up with the four functions of any settlement:

- Dwelling

- Work

- Recreation

- Transportation

One main belief of le Corbusier was that densities weren’t a problem in themselves and that the real issues of cities were the small streets and the failure to provide the proper surroundings for high density living. Cities should be located in parks and not be cities housing parks. He also believed in the separation of traffic and people, with people having walkways in the sky, fast traffic at basement level and lighter traffic at ground level.

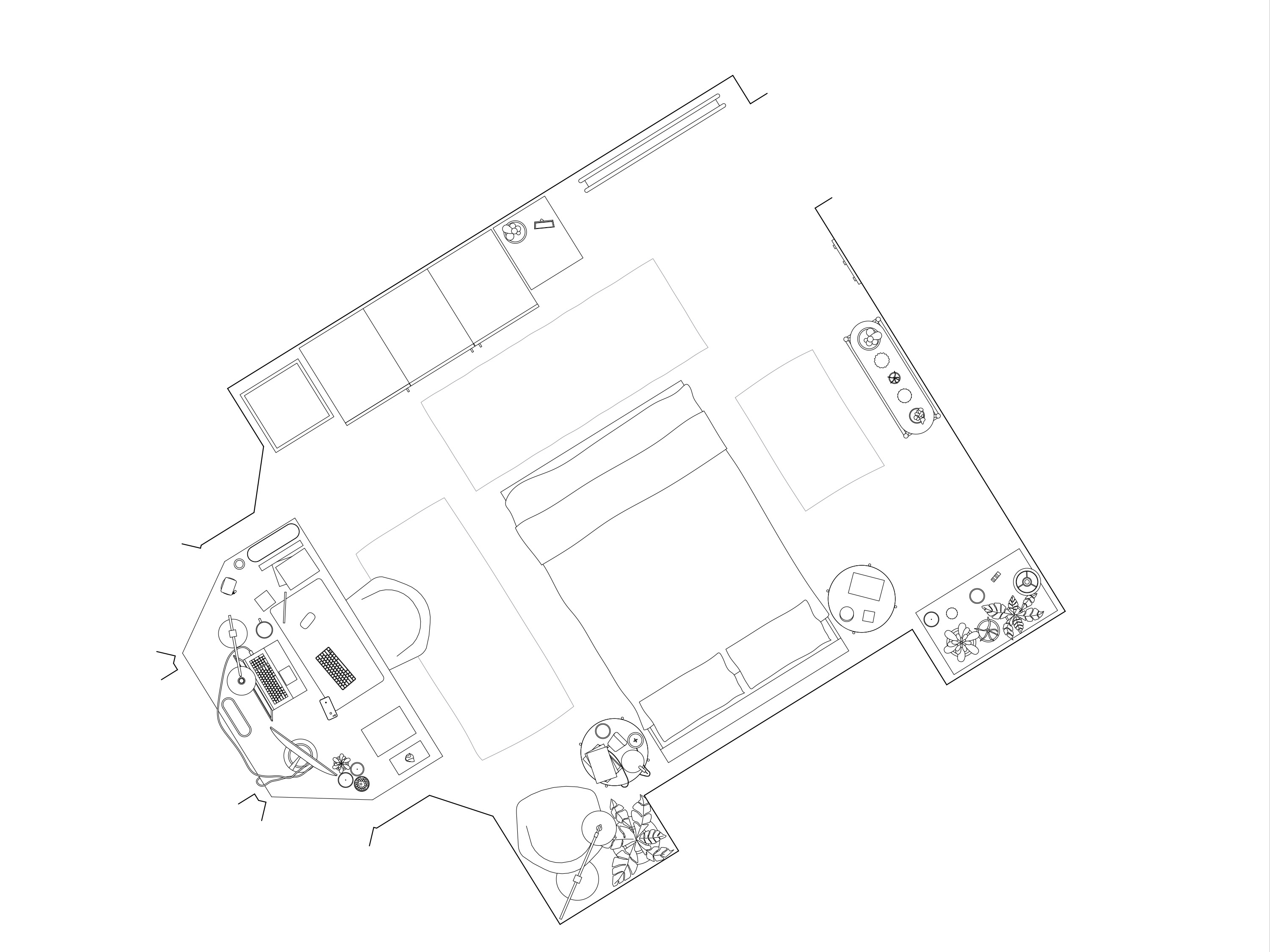

In 1922 Le Corbusier exhibited his design for a city of 3 million inhibitions – Ville Contemporaine de trois millions d’habitants. This proposal had no location, it was merely a “what could be”. This design was rooted in four fundamental principles:

- Decongestion of the centres of cities

- Increase of the density

- Enlargement of the means of circulation

- Enlargement of the landscaped area

This city would have transportation as its centre to accommodate for the future, a vast array of underground trains and platforms for flying cars to land on. The city would expand out from a commercial centre which would contain twenty-four 200-metre-tall glass towers, each housing five to eight thousand people surrounded with ample green space. This would lower into a 50-metre-tall expanse of pre-fabricated apartments known as “unites”, which would hold 2,700 people in each block which would act as a village to house the day-to-day amenities such as cafes and launderettes on the ground floor and a shared swimming pool and nursery on the roof. The city would continue to spread out to house a more rural community on the boundary of the city.

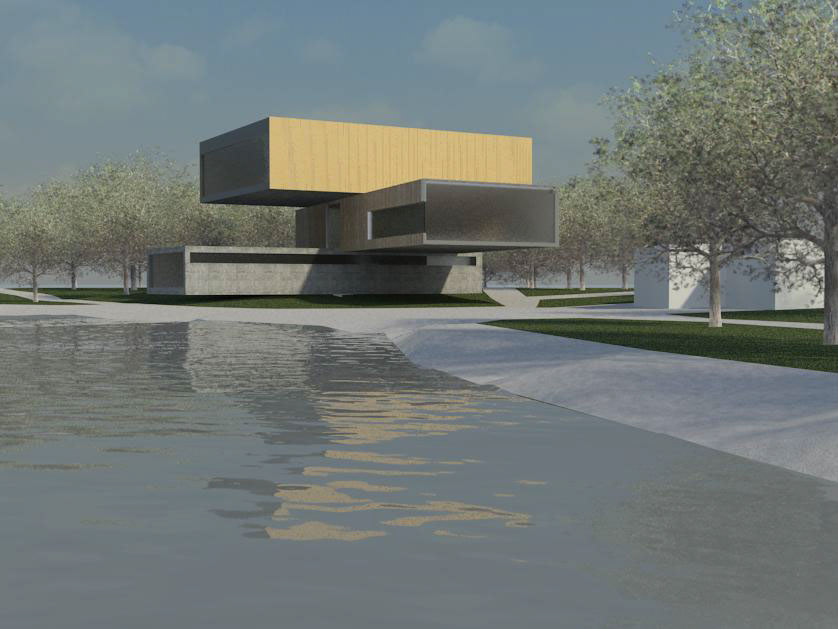

Figure 1 Villie contemporaine de trois millions d'habitants, © FLC/ADAGP

Le Corbusier’s plan for Ville Contemporaine was without location, it was without scope, it was a concept. However, in 1925 Le Corbusier came up with Plan Voisin, to be located on the north bank of the Seine, which would have involved completely demolishing some of Paris’s oldest and most loved streets. However, as Le Corbusier’s view these were overcrowded – “destruction of areas which for the most part are overcrowded and covered with middle-class houses now used as offices” [3], the design would include new roads which would work to take other traffic away from the rest of the city. By replacing the overcrowded low-rise buildings with sky-scrapers, Le Corbusier could open up the city and give the residents of Paris a public realm; only 5% of the master plan would be taken up with buildings, and the crowded city would become a parkland and roadway for the future.

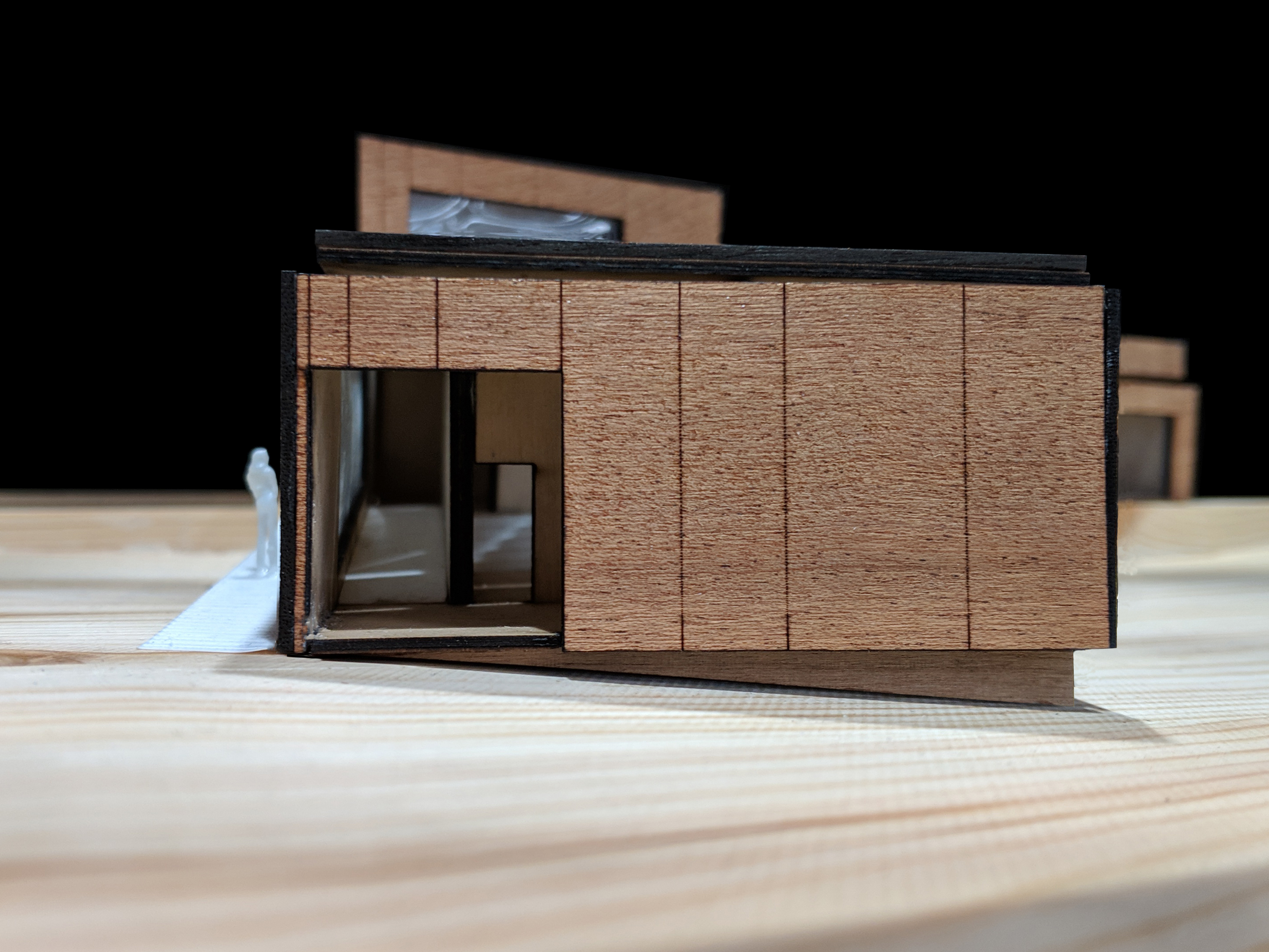

Figure 2 Model showing plan voisin, © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / F.L.C.

For Hilberseimer regulations were everything; he felt that in Germany, building codes were applied with little care and thought, he felt this led to an undesirable mix such as factories next to residential areas, and made each separate area less efficient, and he thought urban planners should have a holistic plan of the city and have their zones work independently. Perhaps one of the biggest shocks that Hilberseimer suggested was that the city centre should play a less vital role, an objection he had to a city based on a centre, working its way out in long twisting fingers, was that the city could only expand so far - “this is also not a final solution but only a provisional remedy, which expires when the growing city has reached a certain size. Then this sort of extension is like-wise no longer a fundamental improvement, but only an attempt at renovation made in the spirit of a compromise” [his book]. Hilberseimer took after Otto Wagner, whose view was that “the city’s fundamental asset was no longer the buildings, but rather the dynamism of the traffic system whose logic shaped the urban form” [4]. Perhaps Hilberseimer thought along the same lines as Le Corbusier?

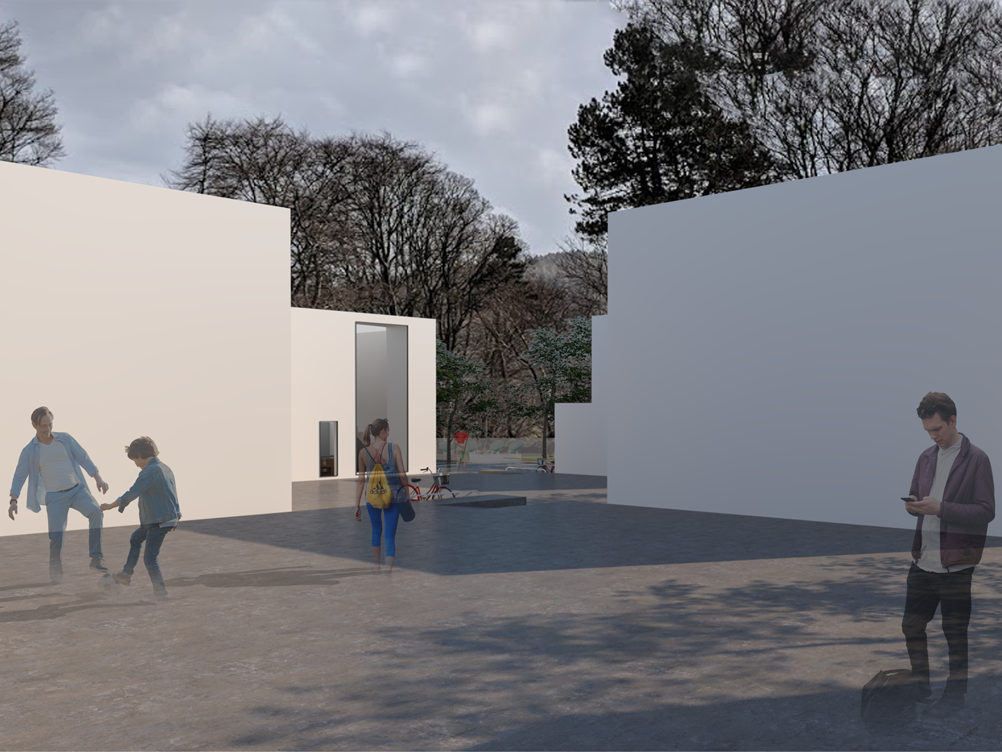

Figure 3 Painting of high-rise city, art institute of Chicago

Much like Le Corbusier, Hilberseimer theorised the utopian city as an entity before applying this vision to a place, and the result of this was his High-rise City. One of the main objections which Hilberseimer had of Le Corbusier’s Ville Contemporaine was that it was a satellite city which, firstly, could not expand and, secondly, could not cope with the traffic which it would face. Hilberseimer designed his city to be “an organization scheme of relations between parts” [5]. This meant that all housing was uniform, as with this would come a stronger collective identity; this city was a socialist city. High-rise City was designed to be a vertical city, people would live above their workplace and all daily activities would follow this vertically, while the horizontal would be space to circulate. This in Hilberseimer’s mind solved the problem of the satellite cities. The commute in High-rise City would be simple: the entering of a lift, listening to a few brief seconds of utopian music before having your workplace open up to you and invite you in to help fuel your socialist society.

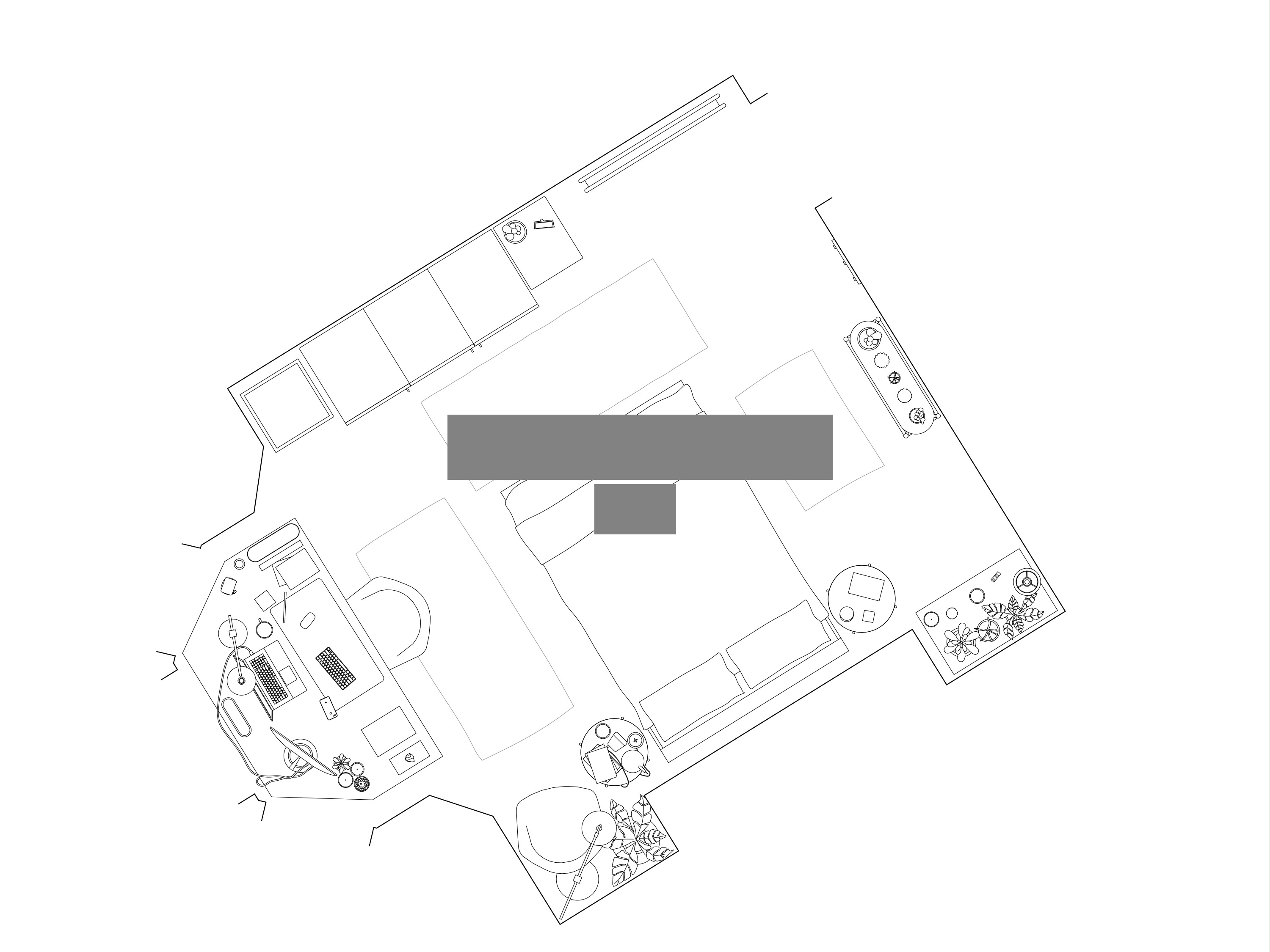

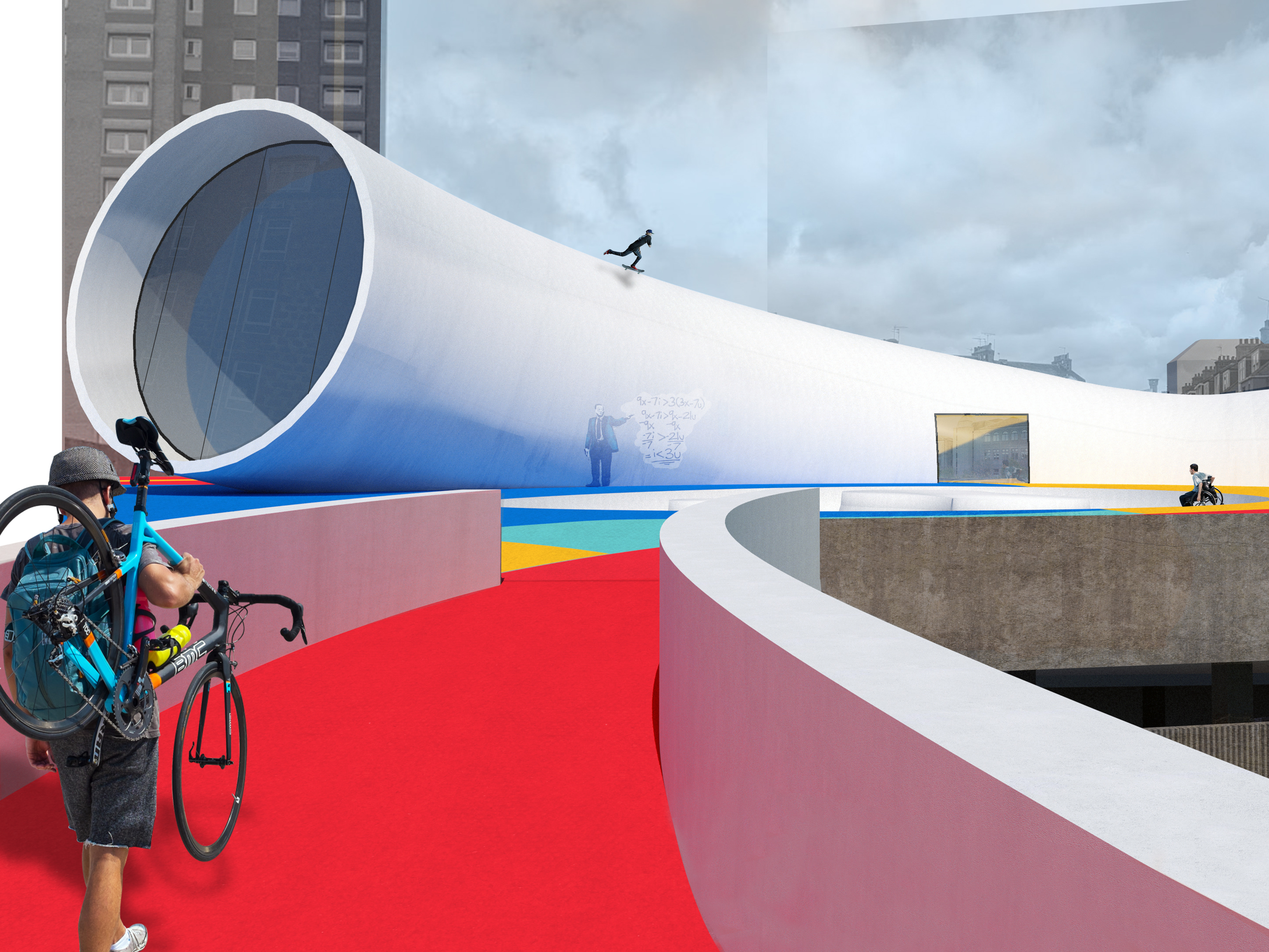

Figure 4 Drawing of Das ungebaute Berlin

Much like Le Corbusier, Hilberseimer applied his vision for a utopian city to his capital – Berlin. The place in question was the centre of Berlin. What was the main objective? This was to design an adequate space for both residential and business, as just a slap-dash mixture of the two does not satisfy either. This was achieved by building two cities on top of each other, the business zone taking up the bottom of the 600 by 100-meter-deep buildings, with two wings on either side of these blocks housing residential spaces, the spatial plan of which is more like a hotel than an apartment. Hilberseimer’s plan was to create a city centre which could function as a new rational system which could be expanded across more of the city centre or even further out. The transportation layout in this scheme was future-proof, as roads were at both basement and ground level, however more space was available if in future an elevated roadway was deemed necessary. Le Corbusier designed his city for the future but the near future, while Hilberseimer sought to design a completed city.

These two designs for European Utopias are both trying to solve the same problems; Le Corbusier designed a radiant park city, designed for a fixed number of people, and Hilberseimer designed an expansive grid system which aims to rethink human movement and proposes the ideal of vertical living, leaving horizontal movement just for travel. These two cities can perhaps both be best described by their designers: Le Corbusier, a “technological Utopian” who “invoked the spirit of classicism and geometry” [6], whose city was thoughtfully zoned and who placed an importance on the classical orders, civil and culture spaces, and in contrast Ludwig Hilberseimer, more of an urbanist than architect, putting more of a focus on the transport, placing the resident second, behind the car, the train, and the plane, and opting to house people in a socialist collective architecture, void of charm and void of the essence of a city. Le Corbusier knew that a city was not just a group of buildings and roads but a unique character, a hidden spirt, and a bringing together of individuals.

Both were visionary individuals who challenged much of the accepted order; for example, Corbusier believed that the size of the house in which people lived should be determined by need rather than wealth. Hilberseimer felt that safety should be paramount, that children should be able to walk to school safely. The plans which they produced for Berlin and Paris respectively, although not actually used, have nevertheless greatly influenced much of current architectural thinking and practice.

Quotations

[1], [4] – AURELI, P, 2011. Architecture for Barbarians: Ludwig Hilberseimer and the Rise of the Generic City. AA Files, (63), 3-18.

[2] – FISHMAN, R., 2016. Urban utopias in the twentieth century. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

[3] – LE CORBUSIER., 2013. City of Tomorrow and Its Planning. London: Dover Publications.

[5] – VELASQUEZ, M. and BARAJAS, D., 2008. Hilberseimer: Radical Urbanism [ebook]. [online]. Ulm: A-U-R-A. Available from: http://streaming.uibk.ac.at/medien/c822/c82231/TXT/Essays/ARCHITEKTURTHEORIE.EU%20Hilberseimer%20100dpi.pdf [Accessed 27 March 2019].

[6] – COLQUHOUN, A., 2006. Modern architecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Other sources

Merin, G. (2019). AD Classics: Ville Radieuse / Le Corbusier. [online] ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/411878/ad-classics-ville-radieuse-le-corbusier [Accessed 27 Mar. 2019].

BOESIGER, W., & JEANNERET, P. (1964). Le Corbusier et Pierre Jeanneret: oeuvre complete 1910-1929. Vol. 1 Vol. 1. Zurich, Les Editions d'Architecture.

CHOAY, F., 2019. Le Corbusier | Swiss architect. [online]. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Le-Corbusier [Accessed 27 March 2019].

GALLAGHER, D., 2019. Le Corbusier. [online]. OpenLearn. Available from: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/heritage/le-corbusier [Accessed 27 March 2019].

Ludwig Hilberseimer | German urban planner, 2019. [online]. Encyclopedia Britannica. Available from: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ludwig-Hilberseimer [Accessed 27 March 2019].

BLAKE, P., 1997. No place like Utopia. New York: W.W. Norton.

JORDAN, R., 1972. Le Corbusier. London: J. M. Dent.

HILBERSEIMER, L., 2012. Metropolisarchitecture and selected essays. New York, NY: Gsapp Books.